Kalliope Muse speaks to me

Emigrée from GR

Masterpieces of the Picture Gallery. Kunshistorisches Museum

Recently I looked at the guidebook for the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. That was an example of an art collection born out of the Erklärung. Now I wish to visit another kind of museum. There is also the dynastic model and one of its best prototypes is the Kunsthistorisches Museum (KHM) in Vienna.

We could say that for the KHM it all starts with this painting, really. Both sitter and painter constitute its foundations. Although we could imagine that Maximilian would have liked for it to have begun even earlier. He was always so keen to aggrandize the supremacy of his family lineage.

Albrecht Dürer. Emperor Maximilian I. 1519.

And the painter, the Northener Albrecht Dürer who was fascinated with the South became one strong model of the international artist. With his travels and stays in Venice he built the bridge that spanned the North and South banks of European painting during the Renaissance. This bridge suited the Habsburg dynasty so very well.

And then this other painting presents to us how the story of this collection continued.

Bernhard Strigel. Family of the Emperor. 1515.

Here is Maximilian’s family. His two grandsons, the older Charles standing in the middle and the younger brother Ferdinand with the arms of the Emperor around him, would split the political power of the Habsburg Empire into twin courts as they both became, in succession, the heirs to the Empire of their granddad. The family would manage their geographic power separately from the two foci of Vienna and Madrid, even if they maintained the same goals. The family remained close. Too close for good biological practices, in fact. Anyway, their allegiances and intermarriages survived for close to two hundred years and left some traces for later times, as we will see later. Apart from their genes, these two courts shared their interest in the arts, and gave birth to twin dynastic museums: the KHM and the Prado.

Apart from the fact that the two sides of the family borrowed art pieces from each other, some particular members began to collect on their own. The first member on the Austrian side who started consciously to accumulate beautiful things was the Archduke Ferdinand II (1529-1595), son of Emperor Ferdinand I (the youngest in the family portrait above) and nephew of Charles V. When he was made Regent of Bohemia he started his collection of portraits and armour and kept it in the Castle of Ambras, near Innsbruck. His choices reflect the tastes of the princes of the Renaissance who enjoyed the pleasures of court life during periods of peace but who still thought of themselves as warriors.

The next self-proclaimed collector was the Emperor Rudolf II (1552-1612), grandson of Ferdinand I and nephew of the Archduke above. Rudolph was a peculiar character. Born in Vienna, he was then sent for a while to the cousin court, from where his mother originated and where his uncle Felipe II reigned. There he learnt to love Titian and Bosch. And when he went back home and became Emperor he had the power and the means to pursue his interests.. He was and is judged, however, to have been a dreadful regent and politician. He got into serious trouble with the Turks and eventually with his own people who changed their allegiances to support Rudolf’s brother, Matthias. But nowadays Rudolph’s court is greatly valued because it was friendly to the sciences and arts. Posterity, particularly foreign posterity, is grateful to Rudolf’s housing the astronomers Brahe and Kepler and to his adventurous tastes in art. We have grown indifferent to the manner with which he dealt with his Empire and his subjects.

His taste had widened beyond the portraits and armour of his uncle. Despite his times and his family, he remained somewhat aloof to the histrionic religious differences that tore his epoch, and added the beautiful and rich collection of paintings by Brueghel and good samples by Cranach. Art from the Protestant lands was not banned from his collection.

The Breughel room is one of the best in the KHM now. And befittingly there hangs his Babel Tower which could be seen as what would happen to the Hapsburg Empire later on.

Peter Breughel the Elder. The Tower of Babel. 1563.

Rudolf also liked mannered inventions and got paintings like this one.

Arcimboldo. Summer. 1573.

Rudolf’s collection, however, was not entirely protected from Politics and as some of his paintings were in the Prague Castle when later on the Swedes entered the town in the aftermath of the Thirty Years War, and some of the paintings were lost in the looting.

The third kernel of the collection was started by the Archduke Leopold Wilhelm (1614-1662), son of Emperor Ferdinand II and brother to the successor Ferdinand III (1608-1657). If the Thirty Year war had meant losses to the collection of Rudolf (his grand uncle), some of the repercussions of the war created new opportunities for the acquisition of art. As Regent of Netherlands (1647-56) he was in the right place at the right time to take advantage of the continued turmoil in Europe. After the Revolution in England several treasures came up for sale. This time the coveted collections of the assassinated Buckingham (George Villiers 1628-1687), very strong in Venetian pieces, and of the executed Hamilton went up for grabs.

Leopold seized them and he was fast. During only nine years he accumulated 1400 paintings. But not all came from distressed collections. Many works came directly from contemporary painters and for Leopold, like for Rudolf before, the religion of the origins of the art did not matter. Vermeer entered the grouping.

Vermeer. Allegory of Painting.1666.

David Teniers painted Leopold with his treasures. This is a visual catalogue since most of these paintings are in the KHM now.

These three healthy seeds of art collections grew into a full being when they were assembled together and declared a single Imperial property. They were first housed in the Stallburg but somewhat later moved to the Belvedere Palace, where they became available for public visits and we can say that they started their life as a Museum. When Vienna remodelled itself, grandly, during the second half of the nineteenth century and the spectacular Ringstrasse was built, the paintings got their own building. Gottfried Semper was called in and his monumental Kunsthistorisches Mueseum with its lofty entrance, magnificent staircase and lovely floors.

These provided a majestic setting for the televised ballet part of the New Year’s Concert a couple of years ago.

And even if too many things have happened and these two courts are no longer on the map, glimmers of the splendour of those times remain. This morning I see in the press that the Prado Museum opens a new exhibition dedicated to the service Velazquez paid to the family of the King Philip IV. And among the paintings visiting Madrid from Vienna, we have the portrait of the infanta Margarita in her blue dress.

Velázquez. Margarita in Blue Dress. 1659.

This painting forms part of a series that hangs together in the KHM and that were produced at the request of Margarita’s maternal and Austrian grandfather. He wanted to follow how the beloved girl was growing up and was being groomed to marry Leopold the future Emperor. The sequence hangs together in Vienna.

Velázquez had to play the role of Skype for the grandparents.

Now I just have to see when can I go and pay my respects to our visitor, Margarita. She is the one on the cover of this guidebook.

Ruskin's Venice: The Stones Revisited

I just receive this and it looks wonderful.

I just receive this and it looks wonderful. Selections from Ruskin together with his drawings of the discussed building as well as the photograph of the same site taken by Sarah Quill.

He is buried there.

Joseph Brodsky is buried in the Isola di San Michele cemetery in Venice.

He is not alone. Other writers, other artists, also chose to rest there. Diaguilev, Pound, and Stravinsky among others keep him company.

Knowing this while reading his very personal ode to Venice acquires an eerie poignancy and adds a premonitory elegiac tint to his prose. I say it is highly personal because this text does not belong to any particular genre. It is a mixture between a lyrical chant, an analytical and descriptive essay that touches on history and current politics, and a series of loose vignettes of what would have been Brodsky’s memoirs, the memoirs of an exile, of someone who knows that a change of place ruptures one’s life.

The most beautiful parts are the lyrical, because, in waves, they come and go like clear water and mark the pulse of the poet. When the waves retreat they leave drier matter-of-fact passages that shake you and wake you up from the lolling dream. Because Brodsky’s mind is sharp and acute and he shows it in many of his observations -- seen from a side glance.

But the water comes back.

And we learn that his fascination and obsession with Venice was born, in a manner that would have enchanted the Surrealists, out of kitsch objects from his Russian childhood as well as out of a run-of-the-mill book. But then they grew into a fully developed recognition of what beauty is. And love. Since for him love is an affair between reflection and its object. As mirrors, reflection and water are the stuff of our eyes, Brodsky then proposes the most engrossing declaration I have read so far of the power and nature of the eye when searching for beauty. The eye is the most autonomous of our organs because its attention is always addressed to the outside. Except in a mirror, the eye never sees itself. And the eye looks for safety and this it finds it in art, in Venetian art.

And thus he finishes:

Water equals time and provides beauty with its double. Part water, we serve beauty in the same fashion. By rubbing water, this city improves time’s looks, beautifies the future. That’s what the role of the city in the universe is. Because the city is static while we are moving. Because we go and beauty stays. Because we are headed for the future, while beauty is the eternal present.

And the city and its water left in Brodsky their mark and as he thought that love is a one way street that is where he has stayed.

PS. I wish to thank Geoff Wilt for drawing attention on this book to me.

Mon Paris et ses parisiens. Tome II: Le Quartier Monceau

I received this yesterday. Only 500 books were printed in 1954. I have found and ordered the previous volume: Quartier de l'Etoile.

I received this yesterday. Only 500 books were printed in 1954. I have found and ordered the previous volume: Quartier de l'Etoile.

Gemäldegalerie Berlin. (Prestel Museum Guides.)

Francesco de Giorgio Martini. Architectural Veduta, 1500.

Having a fair collection of books on individual Art Museums, usually purchased on my way out from a visit and which then go straight into hibernation in my shelves, I decided that it was time to revisit those museums from my armchair and read and look more carefully at those wonderful illustrations.

I started with my pocket guide to the Berlin Gemäldegalerie.

The Gemäldegalerie is a fascinating museum because unlike many of its cousins in the European capitals, its foundations are not grounded on a princely or dynastic collection. Its origins are ideological. Born out of a didactic aim, proper fruit of the Enlightenment or Erklärung ideas, it was conceived to educate the people. And this accounts for the somewhat different array of periods represented. Most of those cousins had as the core collection the High Renaissance and the Baroque. Those were the times during which Monarchs and Princes were the major patrons as well as the great collectors. They commissioned or bought only what they liked and their tastes were mostly contemporary and reflected the current fashion. Or rather, they set the fashion in art and they made the artists. And as political patronage was political propaganda, they procured portraits or political allegories or depictions of history, as well as more private or religious pieces that would promulgate benevolence for them in the heavenly spheres.

Instead, the Gemäldegalerie began with a rational plan. Aloys Hirt (1759-1837), first professor of art history in the University of Berlin, was the first of its conceptual architects. The aim was to put together a good distribution from a complete as possible array of periods and styles as could be managed. The architectural architect was Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841). He devised the spectacularly grandiose first home of the collection, the Altes Museum. To these two personalities the art historian Gustav Friedrich Waagen (1794-1868) added his honed connoisseurship abilities.

As these were also turbulent times, some collections came up for sale. The first one that could be approached was that of Vicenzo Giustiniani, a Genoese banker from the seventeenth century. A considerable chunk of around 160 pieces from the Rome assemblage were negotiated and purchased in 1815 in Paris with a good selection of the Primitives and Early Italian Renaissance an Caravaggio pieces. The funds were provided by the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III(1770-1840) whose interest in the project was won by the pioneering sponsors. Soon, another selection from another existing collection was added. This time it came from the British businessman Edward Solly (1776-1844) whose family had based their trade in the Baltic coast and who were living in Germany. It was thanks to Solly’s selection that Berlin now has such a fabulous assortment from the very early Italian and Netherlandish Renaissance. Running into some financial difficulties, Solly had to sell his three thousand paintings. Close to seven hundred ended up in this Berlin collection.

When Berlin became the capital of a united Germany and the growth of the industrial base generated considerable capital, the impetus of this still new museum in Berlin received more support and acquisitions continued. Prosperity during these dynamic and agitated times was not for everyone, however, and another failed private enterprise generated another acquisition opportunity. Barthold Suermondt (181-1887) also had to sell his treasure. Amongst his jewels there was Van Eyck’s delightful Madonna in der Kirche.

This was also the time when the Art historian Wilhelm von Bode (1890-1920) left his mark. The rich Rembrandt selection bears his print and the enlarged Netherlandish selection was promoted by his curator, the colossus of Art History, Max Jakob Friendländer (1867-1958). And the building, to which the much larger collection had to move, bears also Bode’s name. From 1904 stands The Bode Museum at the Northern tip of the Museum Island.

During WW2, a considerable amount of the very large paintings were lost since no appropriate shelter could be found for them. After losing more pieces to the Russian and American looters, the collection had to be, like other things and hearts in Berlin, divided into a Solomonic and unsatisfying twosome. The Eastern collection remained in the Bode museum while the Western moved to the Dahlem building. Not until 1989 was the collection united again in the Kulturforum.

There was a great deal of noise last year because the collection was to suffer yet another transfer to a projected new building in the Museums island and surrender its current site to the Modern collection. The latter has received a large donation by Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch composed mostly of Surrealist and Expressionist pieces. The conditions of the bequest seemed to require the site where the Old Masters have their home. A large uproar in the art and culture circles succeeded in halting this idea because it would have meant sending to storage about half of the Gemäldegalerie collection for close to a decade.

But the dilemma between the preeminence of the Old and the New Masters may not have finished yet.

If part of the Gemäldegalerie collection is to undergo a more prolonged hibernation than by Museum books, I shall have to leave my armchair and go and visit that beautiful selection of paintings again before they are locked up.

Out of the 300 paintings selected in this comfortable to carry, but a bit too small to fully appreciate book, I have selected a few for my review.

Jan van Eyck. Madonna in the Church c. 1425 (detail)

Lucas Cranach the Elder. The Fountain of Youth, 1546.

Jan Vermeer. The Glass of Wine, 1661.

Rembrandt. Self-Portrait with Velvet Beret, 1634.

Caravaggio. Cupid as Victor, 1601.

And I just hope that now Amazon does not delete this review - it may not like Caravaggio's nude.

Femmes peintres et salons au temps de Marcel Proust: de Madeleine Lemaire à Berthe Morisot

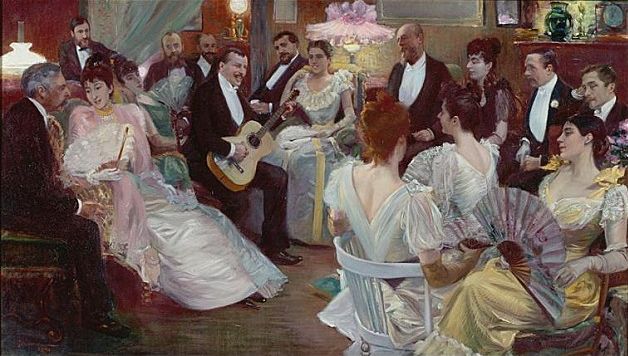

Une chanson de Gibert dans le Salon de Mme Lemaire – Pierre-Georges Jeanniot (1848-1934).

This painting is the unfolded cover of the catalogue to an Exhibition presented at the Musée Marmottan Monet in 2010. Unfortunately I did not visit the display, but I am fortunate in that I can treasure this catalogue.

There are two aspects I want to discuss in this book. The initial and obvious one is its contents, but I also want to consider the startling effect that some of its contents have had in the 2013-The Year of Reading Proust, when I posted them there.

As the preface clearly states, this exhibition places itself in one of the trends that Gender Studies has originated. Its objective is to examine the role of women in the art and literary world during the second half of the nineteenth and first decades of the twentieth century in France. A pioneer in this direction was the American Art Historian Linda Nochlin (b. 1931), but this exhibition follows closely the steps of another one at the Centre Pompidou about a year earlier (elles@centrepompidou.fr/blog/).

The main focus is a group of female painters as well as a survey of the historical circumstances in which their artistic activity could flourish. Given that the École des Beaux-Arts was not opened to women until 1896, a more private setting would have allowed these women to explore their interest and abilities in the arts. These were the Salons. The relevance of these exclusive and personal gatherings in the French cultural scene was not new, but during this period they acquired new characteristics as the women gained ground and were moving towards professionalism.

And it is in this particular context that Marcel Proust emerges. His master work La recherché du temps perdu is loaded with recreations of the artistic and private social circles in the Paris of the Third Republic. And even if he did not develop a full Salon-literature in the tradition of Diderot and Baudelaire, he published several articles on these Salons in major newspapers before he started his macro novel.

He had been there. And as he had seen and listened, he had also observed and identified the feminine coding of such circles. He recorded them.

And it is through Proust’s lens that this exhibition presents these feminine French Salons.

LES SALONS

Four salons are selected in this book. They were not the only ones. There was a myriad of them in the Paris of the time and many were located in the Monceau area. But as this exhibition is presented through Proust’s lens, some are just mentioned in passing, such as the one organized by Madame de Caillavet. Even though Proust attended it, it was her exclusion of musicians that has excluded her Salon from this exhibition.

La princesse Mathilde (1820-1904).

The relative of the two Napoleon Emperors had a Salon with two editions. She began during the Second Empire in the Rue de Courcelles but succeeded in maintaining its importance during the Third Republic when she moved it to the Rue de Berri. Proust attended the latter together with his friends Reynaldo Hahn and Jacques-Emile Blanche. And after writing his Un salon historique in 1903, he also included her, as herself and as a model of the still lingering Empire society, in La recherche.

Apart from some astounding portraits, the exhibition displayed a magnificent fan, in a Japanese style, adorned with the signatures of forty-nine celebrities amongst whom we can recognize a Goncourt, Maupassant, Dumas, Zola, and Anatole France. We could try to picture her in her noble surroundings airing herself with the minds and creations of these writers and musicians and painters.

I also remember her as major figure in the success history of the House of Cartier. It was she who introduced the objects of still inconsequential importance, and fabricated by still-with-no-name goldsmiths, to the Empress Eugénie. The walking canes or tea sets opened the way for subsequent treasures and patrons and for the coining of the name in luxury.

Princesse Edmond de Polignac (1865-1943).

Winnaretta Singer could have stepped out of a Balzac novel. This is industrial money marrying into the secluded nobility. By marrying Edmond de Polignac, they could have also been characters in the Sodome et Gomorrhe volume, since both were homosexual.

Proust visited this Salon too, when he was introduced by the Count Robert de Montesquiou-Fézensac (by spelling out the full name, I am showing I do not belong to those circles, as Marcel Proust would have noted). This Salon was notorious for its modernist tastes in Music. If the pure Romantic repertoire and musicians (Berlioz and Liszt) were to be expected chez the previous Princesse Mathilde, at the Polignac’s, the sounds heard were those produced by Fauré, Chabrier, Ravel and Falla, or the older French music as the modernists revived the interest in Couperin and Rameau. An opera by the latter was performed at the château in the Avenue Georges-Mandel.

And it is in honour to the music that Proust dedicated his writing on her Salon from 1903 Le salon de la Princesse Edmond de Polignac. Musique d’aujourd’hui echos d’autrefois, even though he could have concentrated also on one of her Monet paintings, since he thought that she had one of the most beautiful Monet his eyes had ever set eyes upon.

Madeleine Lemaire (1845-1928).

Her presence in this exhibition is on two counts. She is one of the studied Painters and she was also a Salon hostess. And yet, this book indicates that, until recently, she has been a figure more for the literary rather than for the art historians. In posterity, her name has been attached to the names of Dumas, Montesquiou, Anatole France and Proust, rather than to her canvases. This exhibition is trying to correct that, also in two counts.

She was a woman who got up at dawn to spend the full morning painting and reserved a couple of afternoons for her social projection. And she painted not just flowers but wonderful portraits too. Her salon had a strong musical interest as well, and was particularly strong on theatre, which was one of Proust’s major interests.

And even if she can be associated closely with Proust, since not only did she welcome the writer often at her Salon and at her summer house, but also illustrated his first book Les plaisirs et les jours, this book and exhibition however dethrone her from her established position as the main model for Proust’s Mme Verdurin.

This is a portrait of Réjane on her Château de Réveillon, where Proust and Reynaldo Hahn stayed as Lemaire’s guests.

Marguerite de Saint-Marceaux (1850-1930).

And for me the revelation of this exhibition is Marguerite de Saint-Marceaux. Her Salon lasted for about fifty years, but its heyday was from 1892. Born into a family of artists and marrying artist twice, she also was engaged in writing her diary. She has left us 1400 pages of a diary covering the years 1894-1927, which must be a fascinating record of Parisian cultural life, and which I plan to read.

This catalogue presents her as the main model for Mme Verdurin given that her Salon in the Boulevard Malesherbes was the most consciously dedicated to the arts. The dynamics of her Salon were also different from the others. She received her noyeau of about only twenty selected fidèles for dinner while the subsequent music recital would welcome a few more visitors. She directed a cultural agenda with an identified topic such as the discussion of a given book or painting or the listening of a particular piece of music, with Modernist music as center stage.

But what is most extraordinary about her salon, and which approaches her the closest to the peculiar personality of Mme Verdurin, Proust’s creation, was Marguerite’s antimondain stand. She openly displayed the contempt with which she contemplated the mondain or high nobility circles. This setting herself and her followers apart, was to be revealed by a different dress code as well. The members of her Salon were to dress “de travail” rather than in full gala. Thereby they would show their superior distinction in this more dignified fashion.

LES FEMMES PEINTRES

Having visited the private Salons where women could develop their art interests and abilities, the exhibition then centers on a few of these painters.

Of these the most outstanding is Berthe Morisot (1841 – 1895), who does not need rehabilitation since she is already part of Mount Olympus of Art History. It is laudable that the exhibition has not centered on her, even though the Musée Marmottan houses a considerable collection of her paintings.

Instead we welcome the attention paid to Louise Abbéma (1853-1927), to Louise Catherine Breslau (1856-1927), to Mathilde Herbelin (1820-1904), and of course to our Salon hostess Madeleine Lemaire (1845-1928).

Memorable is Abbéma’s pastel portrait of Sarah Bernhardt.

But the one I walk away with, and in particular her drawings, is Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899). Her sketches of lions, of the hooves of horses, of running dogs are unforgettable in their simultaneous delicacy and power. Her connection with Proust however, escapes me, but no matter, her non-feminine art is a good companion to the writer’s exploration of the boundaries between the sexes.

Seeing Bonheur’s drawings now reminded me of a recent visit to the D’Orsay Museum. I stood for a while in front a huge painting of cows walking and advancing diagonally towards the viewer through mud of a deep chocolaty brown. I was mesmerized by that mud protruding out of the canvas. Who on earth would be willing to deploy so much effort and attention (chore, exertion, endeavour) to such a scene? Imagine when I surprised my ignorance and saw in the label that this painting was the result of the hard labour of a lady with the dainty name of Rosa Bonheur.

Unforgettable.

PROUST GROUP

And now we come to my second consideration, and that is the proposal of Saint-Marceaux as the main model for Proust’s Mme Verdurin. The catalogue acknowledges that Proustians follow Tadié’s identification of Madeleine Lemaire as the main inspiration for the Patronne, but shifts the attention from Madeleine to Marguerite. The main basis is the very artistic focus of the Salon and its self-conscious and self-limiting identification as antimondain as stated above. There is also a reference to a letter written by Lucien Daudet to Marcel Proust in 1922 in which it seems he identified Marguerite as “une Verdurin beaucoup plus Verdurin”.

The Lemaire-as-Verdurin concept is so entrenched amongst Proustians, however, that this proposal has received opposition in the Proust Reading Group.

My stand on this is also what Proust defended. That is, his characters were the result of a multiplicity of observations as well as his own creative abilities. In the particular case of Mme Verdurin, she is too much of a caricature to accept her as a literary mirror of anyone in Proust’s life.

This debate has made me think about the dynamics of academic research. I can imagine how the top rank awarded to Lemaire could be made by scholars who may not be as strong in the knowledge of Salons as they are on the particularities of the novelist. While now their proposal is questioned and rectified by scholars who have concentrated on Salons. The latter have gained ground lately with the backing from Gender Studies, as Salons were the territories of women.

The work by Anne Martin-Fugier and Laure Adler are often cited in this catalogue.

But as I said, for me Madame Verdurin is Madame Verdurin, the Patronne.

There is just no one like her.

La baronne et le musicien: Madame von Meck et Tchaïkovski

From the F minor of Symphony nº 4 to The Queen of Spades

What a perplexing relationship between the Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) and his compatriot Nadezhda von Meck (1831-1894), his financial Muse! Their correspondence, copious and out of which over a thousand letters have survived, constitutes the score of a progression as it proceeds along all the necessary chords from an abstract and suggestive f minor tonality in full symphonic deployment to a staged concrete drama that ends in Death. And I don’t think there is a spoiler here.

This account has been offered to us by Henri Troyat (Lev Aslanovitch Tarassov – 1911-2007), a Moscovite who arrived in France with his family at the age of six, and where he grew to be a Member of the prestigious Académie française by 1959. He is well known for his prolific output of fiction and biographies. His prose flows like clear water and the richness and appropriateness of his vocabulary baffles me. His command of Russian also means that, as he listed in the bibliography, he had studied the three volumes of the correspondence (in the original and covering the years 1877-1890). His ability to stand astride two cultures accounts for the popularity of his biographies of both French and Russian political and literary figures.

Troyat focuses on the epistolary relationship of this peculiar couple and has taken, principally, her standpoint. Very little is discussed of Tchaikovsky’s music except tracing his production as it occurred across the years. Rather than to Tchaikovsky, on whom so much has been written, I felt a great curiosity to find out more about this phenomenal Madame von Meck.

Nadezhda was the daughter of a well-to-do family and married at the age of sixteen Karl Otto Georg von Meck, an Engineer and civil servant, and twelve years her senior. They had eleven children even if according to Troyat there was no true sensual love between them. So far so good; nothing extraordinary in this.

What was outstanding is that at some point this woman convinced her husband to quit his honorable but ordinary job and put all their money, which was limited, into what she detected was a major trend that would transform Russia--and their fortunes. They put their capital in the building of Railways. In twenty years Russia went from one hundred to fifteen thousand miles and two of these expanding Railway networks belonged to this couple. The Von Mecks grew immensely rich.

And then her husband died in 1873.

A widow in her early forties she then concentrated marvelously all her management skills in handling her business and fortune, and her very large household--with a house with sixty rooms and her numerous offspring. She did this with great efficiency, determination, acumen, guile and discipline.

She also traveled greatly. Having her own coach, which fully and comfortably accoutered could be appended to public trains, she zoomed through Europe constantly, spending time in Vienna, Paris, Lake Cuomo, Florence, Nice, Berlin, the Loire valley, amongst other places. In Russia she also moved from mansions in the country to those in city.

And she had a passion. Music. As a no-professional pianist of excellent abilities, she kept, together with the nannies and a full troupe of servants and serfs, some musicians in her household under her aegis. One such was the young French, Achille Claude Debussy, as piano teacher for the children. She had hopes for him: Dieu veuille qu’il ait une parcelle de son (Anton Rubinstein’s) génie. It seems at some point Debussy entertained the idea of marrying one of the daughters.

And it was during one evening in 1878 that she went to hear her friend Nikolai Rubinstein conduct some pieces by the upcoming Russian composer, Tchaikovsky. The piece was The Tempest. If not a lightning, a “coup de foudre”. Il n’y avait plus devant moi La Tempête, l’amour et l’invisible auteur qui répandait autour de lui ces accords merveilleux, capables d’envoûter l’univers et de procurer à l’être humain une plénitude de félicité dans le bien et le ravissement

It is through this musical turmoil that Tchaikovsky entered Nadezhda’s soul.

From that moment began a financial relationship dressed up in epistolary etiquette, refined manners and beauty, yes, also beauty and possibly… some love. The collection of letters is also a treasure of enlightening material for musicologists. These letters accompanied the premieres of the Symphonies, Operas, and chamber music in the main European towns.

FINANCES

The aftermath of The Tempest was a letter from Nadezhda to Tchaikovsky offering him some menial work, such as some musical transcriptions and simple compositions. This was in December 1876. This offer grew gradually but fast for the following two years, until Mme von Meck took over and settled fully Tchaikovsky’s debts. Once clean he was maintained afloat by the establishment of periodic installments on a renewable annual allowance of six thousand rubles when an average (how representatives were “averages” in Russia, the country were dispersion is best exemplified?) salary was a tenth of that amount.

Soon after they met, he got married, and the newly married couple started suffering immediately. And so suffered also Nadezhda , since she was possessive and jealous of everything surrounding her composer. Luckily for her, Tchaikovsky soon felt unbearably trapped in his unsuitable marriage to a woman. Madame von Meck gladly bought back his liberty and paid for the divorce settlements.

She continued to free him from everything else, except from herself. When she settled his debts he was also convinced to leave the Conservatory, with all its distracting duties. All the restrictions for his liberty to dedicate his time for composition she had therefore lifted.

Together with enlightening his burdens, she offered him further free and open and physical grounds for the expression of his creativity. He stayed several times in one of her secluded states. And to top it all off, and now that his time was costless, she also presented more personal tokens by sending him that which would measure the full value of such a treasure: a watch designed by Cartier. He accepted it.

There is always a price to pay, even for money. What she set as her condition he easily, and thankfuly and greedily agreed to. They were never to meet in person. Troyat shows, though, that at a couple of times they almost run into each other in all their crisscrossing of Europe. For her these occasions became a titillating experience. It was so exciting to dare to defy her own rules, the only ones she accepted.

And if their bodies did not meet, their blood did. She maneuvered until she married her son to one of Tchaikovsky’s nieces. Talent and money should entwine. But it was another, sadly, unsuitable marriage.

During this epistolary and financially sound time his music production and fame grew considerably. He was called from London and from New York. And most important, the Tsar became a follower. From 1888 Alexander III offered the composer the annual pension of three thousand rubles a year (generous but still half of what Nadezhda was giving him).

But even if his musicianship was flourishing, and the income this brought supplemented the two steady allowances, his traveling and living expenses climbed faster. Ten years into the period under her financial aegis, he not only needed still her golden letters, but required them faster. By the year he started receiving also the support of the Tsar he requested her a couple of times an advance on the future allowances stipulating as well by when did he want to touch his funds.

These letter extracts are somewhat embarrassing to read.

MUSIC

But all these flows did not fall on deaf ears.

If the encounter was prompted by The Tempest and bolstered by his First Piano Concerto, it was with the 4th Symphony that their relationship was sealed. It was premiered in 1878 and he dedicated it to her.

In one of her letters she identifies the piece as Her Symphony (je veux que cette symphonie soie MA symphonie), to which he adroitly replied that it belonged to Both, since Ce qui représentait une fusion plus intime que celle bénie par l’Eglise et que son amour pour elle était trop fort pour exprimer autrement qu’en musique.

When she received the piano transcription of this piece she could not stop herself from playing it.

Ces sons divins s’emparent de tout mon être, ébranlent mes nerfs, soumettent mon cerveau à une telle exaltation que je n’ai pu dormir ces deux dernières nuits.

She sent him FF 1500 for the publication of the piece.

With this piece their disembodied friendship was confirmed as an abstract confluence of ethereal sounds tuned to a tenuous minor tonality, in which the notes and chords move in a more or less harmonic manner and in a more or less melodic way. This particular Symphony is also constructed, ironically and pertinently, by two main themes that do not seem to conflate nor weld together. Similarly to their souls.

QUEEN OF SPADES

As Tchaikovsky continues his successful career and becomes closer to Imperial power he moves further away from her. Consequently she becomes more and more uncomfortable as she is well aware that her rival is the very Tsar of Russia. When the Emperor proposed to the composer to write an opera based on another of Pushkin’s stories, the Queen of Spades, she tries to dissuade him. Nadezhda does not like opera. Nor did she like Pushkin’s story. And then, he notifies her that the opera is finished. An insulting fait accompli, when before he would discuss with her his musical choices.

She becomes very suspicious. She sees the parallels between the money-driven main character of the story, Hermann, and her protégé, as well as between the Countess, who has the key to his material wealth and herself. And then the curse in the story: one will die because of the other.

She decided to stop her support. After thirteen years. That was September 1890.

The premiere of the Queen of Spades, a few months later, was a success in the Theatre Marie in St Petersburg.

WRONG CARD

But maybe he had played with bad cards.

Just a few days after he premiered the Pathétique in Saint Petersburg, he succumbed fast to the cholera outbreak in Russia. This happened also at the time when the noise about his homosexuality was becoming louder and in a country where such preferences were then a crime and were punished with a Siberian exile.

Did he mistakenly or willingly drink the poisoned water?

And then, only three months later, she also died.

Troyat helps us in understanding her end. He says: “l’homme qu’elle s’est ingéniée à fuir tout en le poursuivant au long de sa route… en disparaissant –volontairement ou accidentellement—il l’a condamnée elle-même à disparaitre.

Having learned more about this unhealthy relationship, there remains, however, a clear beneficiary. Nadezhda von Meck purchased from Destiny the Time that Tchaikovsky’s Talent needed. If she could not buy talent for herself, at least she bought it for us.

Posterity, we, shall forever remain grateful to her.

And to him.

THE KRITIOS BOY

This is Beauty.

Male human Beauty but it transcends the particular.

Contemplating Beauty brings Happiness.

We seek this Happiness, this complete Harmony with one’s Life.

Perfect Harmony is Divine.

Beauty is the Path.

How to find the Path, how to reach the final goal?

And in seeking, we Desire.

Is Art the Artifice that creates the Divine?

Goodness, Virtue, Health, Order, Perfection, Restraint, Discipline. All are required.

Talent has to be wedded to Dignity. Only then is it Moral.

But also Freedom is needed. Freedom from the thinking mind. Freedom in open and infinite spaces.

Simplicity and the Sea.

But there is Time, and Chronos easily brings decay. Or Destiny strikes.

For Salvation the only thing we have to defend us is Art.

And as the sun and its light drag us to the Senses they can also intoxicate us.

And yet, Art — Writing -- cannot reproduce sensuous Beauty, but they will praise it.

How to avoid the lurking Danger?

They are too close to Emotions. Mirrors of Love.

This is Eros, the Divine.

The Senses are the Forbidden Fruit.

Overripe strawberries, already dragging us, with them, into irreversible decay.

Falling.

The Abyss.

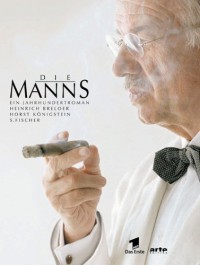

This book is the companion to a TV miniseries produced by the German television and broadcasted in 2001 in three episodes. I have watched the DVD in parallel to reading the book. Heinrich Breloer was both the director and the script writer.

The work is a highly successful mix between fiction and documentary. The fictional side is emphasized by its subtitle: Ein Jahrhundertroman. The dramatized saga has an outstanding cast. The internationally known Armin Müller-Stahl plays the role of Thomas Mann, while the other actors, even if not so well known outside of Germany, are also excellent.

It is a documentary because a fair amount of archival material is cleverly interspersed with the fictional reconstruction. Extracts of older filmed interviews with some of the children--Golo, Monika, Erika--, are invaluable. Older, black and white, vignettes with Thomas and Katia Mann, as well as with other now legendary figures, such as Bruno Walter, Marlene Dietrich, Joseph Roth and Lion Feuchtwanger are also included. Several precious excerpts from historic speeches, such as those Thomas Mann gave when he received the Nobel Prize in 1929; his Deutsche Ansprache in Berlin in 1930; and his communication in English when he arrived in NY onboard of the Queen Mary in 1938 fascinating to watch. The latter is memorable because we see Katia by his side mouthing her husband's words; she had also learnt the speech by heart.

But the most extraordinary presence in this hybrid between Biography and Legend is Elisabeth Mann-Borgese, the youngest of the three daughters, as she accompanies the camera and Breloer when the documentary was filmed. We feel as if she were taking us on the tour of the fabulous Munich house as well as of the other later homes in Thomas Mann’s extended life of exile. Her almost continuous presence along the director, opening up her memories and checking on the reconstruction of facts and personalities, is an invaluable contribution to this filmed document. It is her presence and her oversight that completely validates Die Manns and lifts any possible veil of scepticism on our part. And in so doing the make-believe gains in its simulacrum of authenticity while continuing to render the Manns story so much more approachable.

She certainly becomes the most endearing of the family. She has managed to keep her good spirits in her 80s and often laughs at some of the thorny episodes in the history of her family. We see tears in her eyes when she is read the dedication that her father composed for her mother on her seventieth birthday. We are privileged indeed in having her testimony, for she died about one year after the film was broadcasted.

The first episode begins in the early 20s and covers roughly the period during the Weimar Republic. At that time Mann’s eldest children were in their twenties and the youngest of the six was around five or so. It is during those years that Mann was finishing and publishing The Magic Mountain and received the Nobel Prize. While the father was reinforcing his literary presence, his talented and tormented eldest children, Erika and Klaus, were searching and experimenting with their lives and their artistic and intellectual inclinations. Theirs was a generation of strong beliefs and they benefitted and suffered the colossal shadow of their father. We see with pain how they played openly and defiantly with drugs, with politics, with sexual choices, and shadily with each other. They were caught between the apparently solid, well-established, entrenched and bourgeois Mann household and the abyss. Isn’t this a Thomas Mann leitmotiv?

The second period or fist exile phase shows their life in Switzerland, near Zürich and their arrival in the US. My fascination with the both strong and weak personalities of the two eldest children was fostered in this second episode since it was mostly them, and more effectively Erika, who convinced the father that he had to break openly with the Nazis. She accompanied Thomas to the Neue Zürcher Zeitung in Feburary 1936 to submit his open letter proclaiming his official break and denouncement of the Nazi regime. Fischer Verlag had to move the publication of his works to Vienna.

In the third and final episode the exile continues in the US and it takes place mostly, after a brief interlude in Princeton, in the Pacific Palisades, where figures such as Lion Feuchtwanger, Bertolt Brecht, and Arnold Schoenberg had formed the so called community of Weimar on the Pacific. These were the years of Doktor Faustus, and of difficult personal episodes. In the final stage we follow the Manns as they surreptitiously leave the US back to Switzerland. They recognized early on the practices of political oppression that were growing during the McCarthy era. It is in Switzerland, the final home, where Thomas Mann passed away on August 16th of 1955.

As Breuler’s title indicates, his work is about the family. It is unavoidable that the presence of the Noble Prize writer would seem immense. He is repeatedly referred to, in particular by his children, as Der Zauberer, and indeed Müller-Stahl makes his first appearance in the film in the guise of Thomas Mann dressed up as a Magician for a family Christmas party. But the focus of the film is the whole family. We learn a great deal about the six children, and also about the older brother Heinrich. Their lives are marked by the degree of love and attention they received from the father or by how stifling was his presence on their own creative abilities. He was most fond of his two elders, Erika and Klaus, as well as of the young Elisabeth. The other three, Monika, Golo and Michael suffered from being unequivocally neglected. In their interviews Monika and Golo openly express the criticism of their father. This is painful to understand.

The only truly happy one was Elisabeth even if her choice to marry someone thirty-six years older when she was barely twenty is a very tempting piece of information for those who love psychoanalysis. But she had a happy marriage even if the price she paid was widowhood at an early age and the predictable loss of a father for her daughters when they were still very young.

Watching this film we understand that Death should creep up in Thomas’s literary output. Death surrounded the Manns. The two sisters of Thomas and Heinrich committed suicide. So did Heinrich’s second wife, Nelly. And two of Thomas’s sons, Klaus and Michael, also took their lives. In contrast, others could cling to life in the most extreme and perilous circumstances. Monika was with her husband in the ship City of Benares on their way to Canada and fleeing the London bombings, when a torpedo from a U-boot reached their ship. Her husband, the art historian Jeno Lanyi (a Donatello expert) drowned, but she held onto a floating object until she was rescued twenty hours later. This strength in fastening to life, full of hope and desperation is to me unfathomable.

While we learn a great deal about the other Mann members, Thomas remains inscrutable. His cold and distant bearing (zurückhaltend) as well as his fastidiousness and meticulous way of working seem at odds with the depth in the sensitivity of his writing. This film retains the mystery around him. Even when he hears that his son Klaus has taken his life, the camera shows a silent Müller-Stahl stepping back into a shadow that veils and remodels his figure into a dark silhouette. Chilling.

To match the mystery that shrouds the husband, the wife and mother Katia is another enigma. She put up with the husband’s obvious, but obviously hidden, homosexuality. She became a protector of his Diaries when they fell in the hands of Nazi authorities, helping her husband to try and recover them. I was shaken to learn how much she cared to preserve a written testimony that she knew would undo, if read, the happiness of any married woman. She would take her husband’s side in any of the conflicts with the six children. She acted as his tireless secretary and typed and proof-read most of what he wrote. She never seemed to have doubts about him. Her aim was to create the perfect writing environment to her exacting husband, so that he would not feel any signs of exile at his desk, for, as he said, Germany was where he was (Wo ich bin,ist Deutschland). She must have thought that her purpose in life was to be the Wife of Talent. And this she did with unquestionable devotion.

But it is Heinrich for whom I felt the most. Exile in the US was very hard for him. This was in sharp contrast to his time in France, where the culture and the language were highly congenial to him and where he enjoyed the company of friends and of Nelly, his stunning new wife, who if somewhat common, was also young and fun. He spoke no English and, in difference to his brother he did not continue writing in German. His books were not translated and therefore not read. Earning no income he had to rely on his younger brother for financial support. The difficulties for the couple pushed Nelly further along the path of alcoholism to her own end. It broke his heart thoroughly.

This documentary has taught me a great deal but it has also left me craving for more. I am looking forward to reading [b:The Magic Mountain|88077|The Magic Mountain|Thomas Mann|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1347799215s/88077.jpg|647489], [b:Doctor Faustus|34440|Doctor Faustus|Thomas Mann|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1347486711s/34440.jpg|3180640], and Heinrich’s [b:Professor Unrat|1147020|Professor Unrat |Heinrich Mann|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1347324712s/1147020.jpg|1134476], [b:Der Untertan|1509432|Der Untertan (Das Kaiserreich, #1)|Heinrich Mann|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1184464739s/1509432.jpg|1501016], as well as biographies on Thomas and [b:In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain: The Erika and Klaus Mann Story|2187700|In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain The Erika and Klaus Mann Story|Andrea Weiss|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1348577124s/2187700.jpg|216673].

I also have the DVD with Mephisto based on the work by Klaus Mann.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0082736/

This essay, which received the Dámaso Alonso Prize in 2009, explores the artistic relationship between the poet Stéphane Mallarmé (1842-1898), the painter Odilon Redon (1840-1916) and the younger musician Claude Debussy (1862-1918).

The phenomenon of synaesthesia is, therefore, at the core of this study. Artists have been fascinated by the ability of one sensual stimulus to activate a different sense from the one which it is supposed to stimulate. Synaesthesia ultimately refers to the union of the senses that takes place in the brain, as neurons activate surrounding areas. Sounds have colors, texts or smells conjure up images, and stories create their melodies.

Focusing on what must have been fascinating gatherings, Sonsoles Barbosa introduces us to the Tuesdays at Mallarmé’s. These took place in his apartment in the fourth floor of 89, Rue de Rome in the 17è in Paris. The attendants, a rich cast, were Verlaine, Renoir, Whistler, Gauguin, Huysmans, and Manet amongst others. They were nicknamed “les mardistes”. Amongst the bourgeois decoration of this salon there were watercolors, paintings, drawings, engravings or sculptures by Monet, Manet, Whistler, Redon and Rodin. These Tuesdays began in the 1870s but we are invited by Barbosa to enter them in the early 1890s.

This is an intriguing visit and we read not just about the artistic concerns that were the main subject of conversation amongst these figures. We also get snippets of their private lives, and learn, for example, that Mallarmé studied in the prestigious Lycée Condorcet, where Marcel Proust was also educated. Or that the poet became the tutor of Julie Manet, that daughter of Berthe Morisot and Eugène Manet, the brother of the painter Edouard, when Eugène died. And that Mallarmé’s daughter, Geneviève (Ô rêveuse), became the godmother to Redon’s son.

The essay looks at the three vortexes of the triangle separately, and then by couples. These mark the perimeter of the area where synaesthesia is created as if this were the realm of the brain where art lives. And in the middle of this historical triangle is where Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907) resides with his novel [b:À rebours|1312641|À rebours|Joris-Karl Huysmans|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1358735926s/1312641.jpg|306152]. Huysmans, who exalted Redon in his novel, was also the one who introduced him to Mallarmé.

In these Tuesdays the beliefs of the art movement Symbolisme were passionately discussed. The movement has an official start date when its manifesto was published in Le Figaro in 1886. But many of their goals had already emerged in Baudelaire’s Correspondances. This poem conceives of nature as a forest of symbols in which perfumes, colors and sounds talk to each other. Tracing correspondences in the senses, art emerges as the activity that will seek to identify and reveal the hidden reality in the magic forest. And the most appropriate path for art is to suggest, to evoke, to imagine, and avoid the trappings of rationality. And music, the least referential of the arts, reigns supreme.

I am lucky in that I visited not too long ago a wonderful exhibition on Odilon Redon in the Mapfre Foundation in Madrid.

Here is the mini site:

http://www.exposicionesmapfrearte.com/odilonredon/

In this exhibition one could follow very well how in his earlier work, Redon explored the imaginary, the dream and ambiguous world, with his black and white engravings of fantastical beings that existed only in his mind. With these monochrome creations he was trying to move away from the world of the naturalists and their dependence on color. To my mind, though, he was falling prey to the old dichotomy exploited in Art Historical discourse that, ever since the Renaissance, has thought that “disegno” was the art of the mind, while “colore” was that of the emotions. Indeed Redon later escaped from this still academic concept and moved from this:

To this:

And this transformation and rediscovery of color was possible, ironically, thanks to the non-visual art of music. As music looked for alternative harmonies and structures and explored the extreme timbres that could be achieved with any given instrument, it managed to daub color in the sound. And so it gave color back to painting.

It is in the new palette of music that Debussy’s art is better heard. He is the composer who most openly developed an elaborate theory that related music to the other arts. His compositions tried to create atmospheres which also evolved in the continuum of time. And this durée in his pieces was paradoxically and antithetically conceived by his new static harmonies--sounds which float in the air and which take you nowhere except to an internal world of images, evocations and mental climates.

And Debussy’s music became so very attractive to these Tuesday gatherings that it was the considerably older and well established Mallarmé who sought out the younger musician for what became a major collaboration between the two artists.

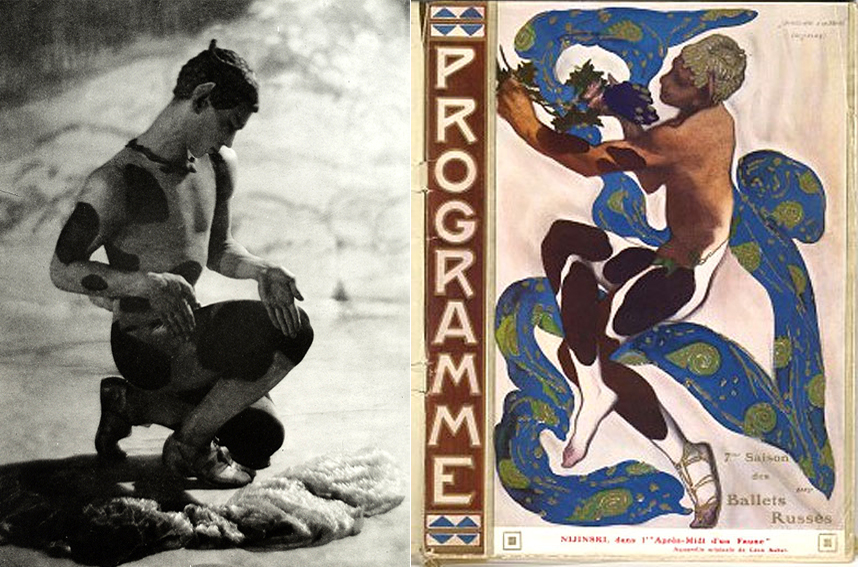

Mallarmé wanted Debussy to give music to his poem L’Aprés-midi d’un faune, written in the 1860s. It had already been illustrated, splendidly, by Manet in 1876. Now it needed sound.

A couple of Manet's images:

In 1894 Debussy composed the Prelude to the poem. His original plan was to write a three-part composition loosely based (could it be otherwise but loosely?) on Mallarmé’s verses, but only the first part was finished. This work could have also been the meeting point of the three artists had Redon succeeded in designing the settings for a Ballet production by Diaguilev and choreographed and danced by Vaslav Nijinsky. But the project for the décors was eventually carried out by Léon Bakst, as seen at the top of this review.

The last few days I have been listening to the symphonic poem during my morning drive. The piece circles around the initial sound of the faun –or flute— while the sweet harps and tremulous strings create the foliage of the warm forest (Baudelairian?) while other inhabitants of the wood instruments accompany and attend to the faun and the suave erotic airs that transpire out of these dream and gentle figures make me feel as if I were driving in a cloud.

Mallarmé’s relatively early death has left us emptiness full of artistic ideas that could not be developed. What we may be missing is hinted by his very avantgardish Un coup de Dés. The way he set out to delve into the possibilities of a poem treating the physical page as if it were a score, positioning the printed words in the page according to intonation, and adapting the typography were explorations that the art world would not see again until the Dadas played with these ideas almost two decades later.

I enjoyed reading this essay even if the language is of the dry academic bent. As these three artists produced not only stunning pieces but also passed on ideas that later creative minds, such as Scriabin or Kandinsky or Schoenberg, managed to inspect even further.

Lovely dream world.

(For those engaging soon in the [b:The Magic Mountain|88077|The Magic Mountain|Thomas Mann|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1347799215s/88077.jpg|647489] read, Debussy’s symphonic poem is one of Hans Castorp’s favorite music pieces).

----------------

POEM

Mallarmé’s Après Midi d’un Faune, in French and English

http://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/L%27Apr%C3%A8s-midi_d%27un_faune

http://faculty.txwes.edu/csmeller/human-prospect/ProData09/01ModCulMatrix/ModWRTs/Mallarme1842/Mal1865Faun.htm

MUSIC

Recording of Debussy’s Symphonic poem, directed by Charles Dutoit.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bYyK922PsUw

Score:

http://imslp.org/wiki/Pr%C3%A9lude_%C3%A0_l%27apr%C3%A8s-midi_d%27un_faune_(Debussy,_Claude)

BALLET with Nureyev

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m7b1FkZYarU

EXHIBITION on Ballets Russes at the NGA in Washington

http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/exhibitions/2013/diaghilev.html

-----------

P.S.

Given the debate that this publiccation has elicited, I decided to move its 4.5 stars to the full five. Plenty of food for thought.

L'école des femmes

What is Comedy? What makes us laugh in theatre? A great deal has been written about this and this review could not do the concept justice. But reading and watching recently a performance of Molière’s L’École des Femmes raised the matter in front of my eyes.

In this play, which as most of Molière’s plays, belongs to the subgenre of a comedy of manners, there are many of the elements that one would expect in funny plays. There are stock characters –following the tradition of the Commedia dell’Arte; there is a great deal of “double entendre”, often through parallel dialogues on the stage and which Marcel Proust could not fail to notice; there is a critique to popularly unpopular professions, such as notaries and other representatives of the law; the plot revolves around the universally farcical figure of the cuckold or “cocu”; there are surprising and magic solutions to tangled up problems that will draw out a smile; there is a bit of slapstick and “coups de bâton” in a purely guignol tradition. All these elements are in the text and the staging can supplement them with mimicry, ridiculous clothing, and doll-like movements.

As was the tradition in seventeenth century French drama, the play is written in Alexandrines and follows the three Aristotelian units of plot, time and place --athough in this play the time unit is as flexible as Dali’s clock. It also follows the more French concepts of “vraisemblance” and "bienséance" (which would have banned Shakespeare) as even the he guignolian coups have to happen off the stage.

This is, and was from its first performance in 1662 onwards, one of the most successful plays by Molière (Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, 1622-1673). At its première it already pleased the King, Louis XIV, gaining his support which later became crucial. L’Ecole des Femmes followed L’Ecole des Maris by one year, and it continued the very popular themes of cheated husbands and of the education of women. It was also successful because it was controversial, highly controversial in fact. And this was easily the best thing for its ticket-office.

Apart from some “sous-entendres” or “equivoques” which at the time seemed to border obscenity too closely (and therefore violating the “bienséance” rule) the play also raised debates on the role and education of women at a time when women were very actively engaging in their literary and intellectual Salons (les Précieuses ridicules). A “querelle” ensued for which the best ghostly protection came from the royal benefactor. Molière replied to the criticisms with another play, La Critique de l’Ecole des Femmes in which a woman and a muse discuss the previous play. Within a few months from the first staging, the two plays were subsequently performed together.

The performance.

I had read this play years ago, but I reread it recently because I was going to attend, two weeks ago, to a performance at the Comédie Française. The theatre founded by Louis XIV, the ghostly patron of significant presence, in 1680.

The mise-en-scène on the 3rd of July at the Comédie Française was by Jacques Lassalle and the two main actors were the formidable Thierry Hancisse (Arnolphe) and the angelical Adeline d’Hermy (Agnès).

I extract no joy in summarizing the story of a novel or play in my reviews, although I am interested in plot dynamics. In this text, the main character, Arnolphe, begins with great confidence on himself and on his aims, but gradually loses control of the situation he himself has created and falls prey in his own net. This turn around constitutes part of the comic (or the tragic?), and follows the tradition of the “Burlador burlado”, a stock figure which originated in the “Don Juan” from early seventeenth century Spanish drama (Tirso de Molina’s “El Burlador de Sevilla”). A superficial reading therefore could take us along a well trodden path of plot and charcter development.

With Lasalle’s interpretation--accompanied by a flawless rendition of the two actors, however, the easy understanding of the play was turned upside down for me.

The Arnolphe I saw turned through the long monologues into the tragic figure of a man who desperately loses his love precisely during the process in which this love captivates him more and more. His obsession in controlling a woman, to the point that he is willing to marry someone ugly and stupid, becomes his undoing precisely because the chosen lady is neither dumb nor hideous. The actor looked exhausted after wrenching out so much anguish out of his text.

But if the above distressing Arnolphe could be extracted from Molière’s text (and he himself was its first actor), we see in Lasalle’s Agnès not just the one that Molière concocted, who rebelled against the string of the puritanical moral laws and who was willing to take risks in order to reject her unsuitable suitor, but one who will also show disdain at her silly and weak beau when he proved not to have her courage.

A memorable play.

A memorable performance.

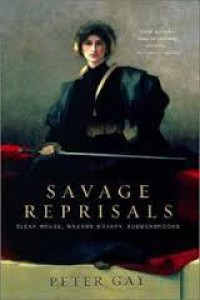

This is a lovely hardback book to hold and touch, with irregularly cut pages and splendid b&w prints at the beginning of each chapter. A disappearing luxury and rare physical pleasure in this advancing age of ebooks.

This is a lovely hardback book to hold and touch, with irregularly cut pages and splendid b&w prints at the beginning of each chapter. A disappearing luxury and rare physical pleasure in this advancing age of ebooks.Peter Gay, whose original name—as Jan-Maat told me-- was Fröhlich, is also a joy to read.

In my academic growth I learnt to revere him and now, years later, I have felt it was time to pick up another of his books and see whether I felt a similar deference. Gay/Fröhlich as a cultural historian is known for his studies of the Enlightenment, of the Weimar Republic, and of Freud and the Victorian Age under a Freudian eye.

I have to admit that I have never been very interested in Freud (I probably share this with many other women) although I may not have approached him properly and I am probably being unfair. Related to this prejudice of mine (and please, do not try to psychoanalyze it) I also tend to get extremely bored by psychoanalytic approaches to novels, or by attempts to diagnose characters and/or authors. Gay’s Freudianism in this literary study is not formulaic nor reductionist. It remains very subtle, and therefore convincing.

Savage Reprisals (what a great title!) consists of three essays on three novels, together with a brilliant prologue and an excellent epilogue. The novels he has selected are Bleak House, Madame Bovary and Buddenbrooks. I have recently read the first and the third, and the second some years back.

In the prologue he identifies three possible values to be extracted out of reading a novel: One as approaching it as a source of civilized pleasures; the second as a didactic instrument for self improvement; and third and final, as a document that opens doors to its culture. He has chosen to focus on the latter, and this leads him to raise several issues related to the writing of history and to the writing of fiction. The forceful realist tradition he adroitly locates in all its international extension, that is, across France, Britain, France, US, Russia, Spain, Germany and Portugal, even if some countries were more precocious than others. In this extended and major Realist current, and he includes also the subgenre of historical fiction, he evaluates the capacity that literary Realism has to portray or represent the authenticity of a given society and the interest it thus raises for historians and fiction writers and or readers.

But it is really the concern of a modernist, Virginia Woolf, who stated that “the foundation of good fiction is character-creating and nothing else”, that serves Gay to introduce his three analyses as samples of fiction that go “Beyond the Reality Principle”.

En each of the three studies, he examines how in these novels, while still embedded and securely placed in a carefully constructed social and political setting, the authors have chosen to dig deeper into their characters with a more engaged psychological analysis. He sees that these three books explore other aspects not normally found in pure realist fiction. One reviewer in this site has complained that there was no connection between the three essays. I disagree. Without going into detail in Gay’s analyses I will just provide what I think links them in his consideration.

In the essay The Angry Anarchist, Gay underlines how in Bleak House Dickens created, in what is still the most “realist” of the three samples, a rather artificial construction, in spite of its apparent mirroring of reality. In this composition, he wielded the portrayal of circumstances to adjust it to an overwrought setting, as well as fashioned his characters either as superhuman or as caricatures, thereby creating a sort of counterpoint that would bring forth his denouncement of a society that he found vicious and worryingly at fault.

The following essay, The Phobic Anatomist, presents a Madame Bovary in which Flaubert, in spite of the obsessive research with which he prepared his novels and all the meticulous minutiae, felt completely free to depart from pre-established frameworks. He flexed his literary powers to create his own rules and pursue his own version of truth. The result is an overstated Emma as a compressed and condensed psyche of discontent.

In the last essay, or The Mutinous Patrician, Gay plots how in his Buddenbrooks, Thomas Mann waved between a realist depiction of the patriciate and an incisive and self-conscious psychological exploration of a few individuals. If Mann liked to vaunt that his Buddenbrooks had anticipated Max Weber and other scholarly sociological studies of a modern Buergertum, he also wrote to his brother Heinrich that “the whole thing is metaphysics, music and adolescent eroticism” in his new novel.

As we could expect, some psychoanalytic considerations are included in all three essays. With Dickens we read about the uneasiness he felt with women and this is explained by his resentment towards his mother and his impossible fascination with his sister in law. With Flaubert we are reminded of his correspondence with his muse Louise Colet and his parallel and periodic visits to whorehouses. And particularly with Mann, his sort of buried homosexuality, and the self-incriminating diaries he allowed to be published an established number of years after his death, are all very attractive aspects for a cultural scholar who has specialized on Freud.

If in his Prologue we saw that Gay introduced his studies on Beyond-Realism through the quote of a modernist, we then see him opening his Epilogue with another quote from another Modernist. Proust is presented as an exponent of the shifting interest on the source of reality in fiction. With him it is the inner being of an individual where his truthful world lies and which also makes history.

MEAN REVERSION IS A BITCH...!!!

There is a concept in statistics, Regression or Reversion to the Mean, which is widely used in a variety of fields of knowledge. It was first realized by Sir Francis Galton, cousin of Charles Darwin, when he worked on the correlation of heights between adult children and parents.

The concept refers to the tendency for any variable which exhibits an extreme value at any point of measurement to move towards the average next time it is measured.

This mathematical tool is used regularly both in Genetics and in Finance Theory. Consequently, it is an apt model for dealing with the Buddenbrooks and their three Fs: Family, Firm and Fortune, and particularly so because the anchor of the family is precisely that: Trading. Their pride was founded upon the buying and selling of grains, and to do so in the appropriate manner with suitable methods, engaging in the right discipline, performing the relevant calculations, exerting their commercial savvy, and adhering to their code of ethics -- all of these constituted their pride and nature.

The novel begins with the second generation of a family and spans five generations. Their business had, however, one generation less. The book tracks the progression of the Buddenbrooks as a function of their prosperity. The characters and their circumstances are factors that exert a force in the success trend of the family.

In the Buddenbrooks the finances and identity of the firm and family are inseparably intertwined. The family’s expenses are expenses for the firm. And profits from the firm accumulated as capital provide the income and living style of the family. The new Buddenbrooks house, the family symbol with which the novel begins, is a monument to itself. Family and firm reside there.

In addition to the launch of the triumphal house the novel regularly pegs the level at which the Buddenbrooks capital stands. They start off with a mark of 900k Marks and the subsequent levels, which can be plotted, guide us as we follow their successes or hardships. Johann Buddenbrook the Younger begins the apprenticeship of his son Thomas by giving a quick review of the big blocks composing their capital. He understands them well. Later on Tom gives the latest balance to his sister Tony, and although the figure sounds reassuringly high to her, he however adds with concern: “we should be at one million” The Buddenbrook capital has stayed sort of flat, which in any progression of prosperity means trouble. As we approach the end of the novel the family is valued at 650k, amount that will however decrease further as the assets are liquidated inadequately.

So, how does this function of prosperity work? The phenomenon of moving back to the Mean irremediably starts and both Genetics and Trading are players in the game.

Depending on their gender and their primogeniture the various members of family will have to perform a different role. The patriarchs, role reserved for the eldest son, are to be the main motor. When this works, it works, but the problem is that its dependency is concentrated on one individual becoming therefore too risky. We see that even the luck of begetting a male son does not guarantee the survival of the genes of mercantile prosperity. Christian turns out to be a good-for-nothing and therefore neither a support nor a back-up to the elder brother in any of the Buddenbrook responsibilities and activities. He becomes a deviation from the trend and a very strong pull away from excellence. Nor is Hanno a healthy alternative to the mercantile model. The boy inherits the artistic inclinations from his mother, but also the lack of discipline that we saw in his uncle. His musical abilities turn out to be good only for toying around with music, not really for playing or composing. He is not, as Tony hoped, a new Mozart. Surprisingly, Thomas Mann does not present the Arts and Music as Saviours for the Buddenbrooks. No redeeming transformation is generated.

The women and daughters occupy a very particular position. The daughters are detractors of a significant amount of the capital, since significant dowries have to be carved out of the sustaining trunk. These side investments are expected to bring back both prestige and an extended business clout with an overall benefit for the Buddenbrooks. In this family the dowries granted out were almost all utter failures. We know that money seduces swindlers like honey attracts flies. And the Buddenbrooks, both the women and the men, suffer as the victims of the Gründlich hoax and of devout greed. The family’s mercantile acumen was not able to detect the money-hunters. In spite of these failures, however, dowries did net in around 89k Marks thanks to the 300k that Gerda brought along when she married Tom.

But it is the concentration on the different roles that the various family members have to play, according to their gender, which increases the probability of failure. Tony is a convinced Buddenbrooks even if she suffered when she sacrificed her Morten. Could she have offered the business support to her elder brother once it was clear that Christian was not capable? Or could she, or her daughter and grand-daughter, have continued the family firm similarly to the way Donatella Versace has? This is hard to say, since after all it was she who persuaded her brother of the suitability of the Pöppenrader deal. Failure or hailstorm, had she been able to participate or take over the business, the probability of survival would have increased. With this possibility barred, the Pöppenrader misfortune takes place precisely and symbolically when Tom’s grandiose house and the Centennial of the firm are celebrated. It marks the resistance point and the decline clearly begins.

But not all the triggers for the Verfall can be found in the family members. The novel gives loose indications of the historical and economic conditions in which we see this family’s progression. We learn that although Johann the Elder expressed antipathy towards the rising Prussia, he had made a great deal of his profits by selling his grains to the emerging Teutonic Kingdom. And several times the Customs Union is mentioned, although we cannot know in what specific aspects they were detrimental for their business. Revolution comes, entertains, and goes. And the new war between Prussia and Austria remains hazily further south. When Thomas refers to the slow pace at which their benefits are made, signalling a business of narrowing margins, we wonder whether there were other factors that were transforming the business profoundly and which he was not detecting. Although the context is included in the novel, we are left with only a very general idea that the rules of the game must have changed and that these have debunked the Buddenbrooks-way. But the book does not offer further detail.

So, what brought the downfall of the Buddenbrooks? It was a joint result of bad luck, some failed judgment, changing political and economic circumstances, and the determinism of social conventions. But when a reversion to the mean process begins, the causes are not important. What is important is that it happens and that it can hurt.

As the Turkish proverb, that Tom quotes, says: Wenn das Haus fertig ist, kommt der Tod, and so the graphs and statistical laws show.

Currently reading

The Aspern Papers (Dover Thrift Editions)

No es lo mismo ostentoso que ostentório: la azarosa vida de las palabras

Dernier Des Camondo

A l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs (A la recherche du temps perdu, #2)

Music in the 17th and 18th Centuries, Oxford History of Western Music Vol. 2

Thaïs (Dodo Press)

Paintings in Proust: A Visual Companion to In Search of Lost Time

The Poetics of Space

The Magic Mountain

Siena, Florence, and Padua: Art, Society, and Religion 1280-1400, Volume 1: Interpretive Essays